Source: Eparchy of Newton

CHEESEFARE SUNDAY IS TRADITIONALLY the last day for eating dairy products until Pascha, as the Great Fast begins tomorrow. This poses a problem in our society where meat and dairy are the substance of every meal. Some people say that they cannot do without meat and so they only fast sporadically. By this they may mean they need protein and are not aware of other sources of protein, such as beans, peas, soy products (tofu), as well as seeds and nuts. But it is perhaps more likely that people miss the taste of meat, fish or dairy products more than their protein content.

As a result many people replace these foods, not with vegetables and grains, but with meat and dairy substitutes made to taste like meat and dairy products. Technically these foods are not meat or dairy – they only taste like them – so they don’t break the Fast. Or do they?

Christian fasting is not based on an avoidance of any foods because they are unclean or taboo in any way. Neither do we abstain from meat or dairy during the Fast for health reasons, out of respect for the creatures that produce them or for environmental concerns, legitimate as they may be. We do not even fast during this season to lament Christ’s suffering and death. As St John Chrysostom wrote, “The Passion is not a reason for fasting or mourning but one for joy and exultation” (Sixteenth Homily on Matthew).

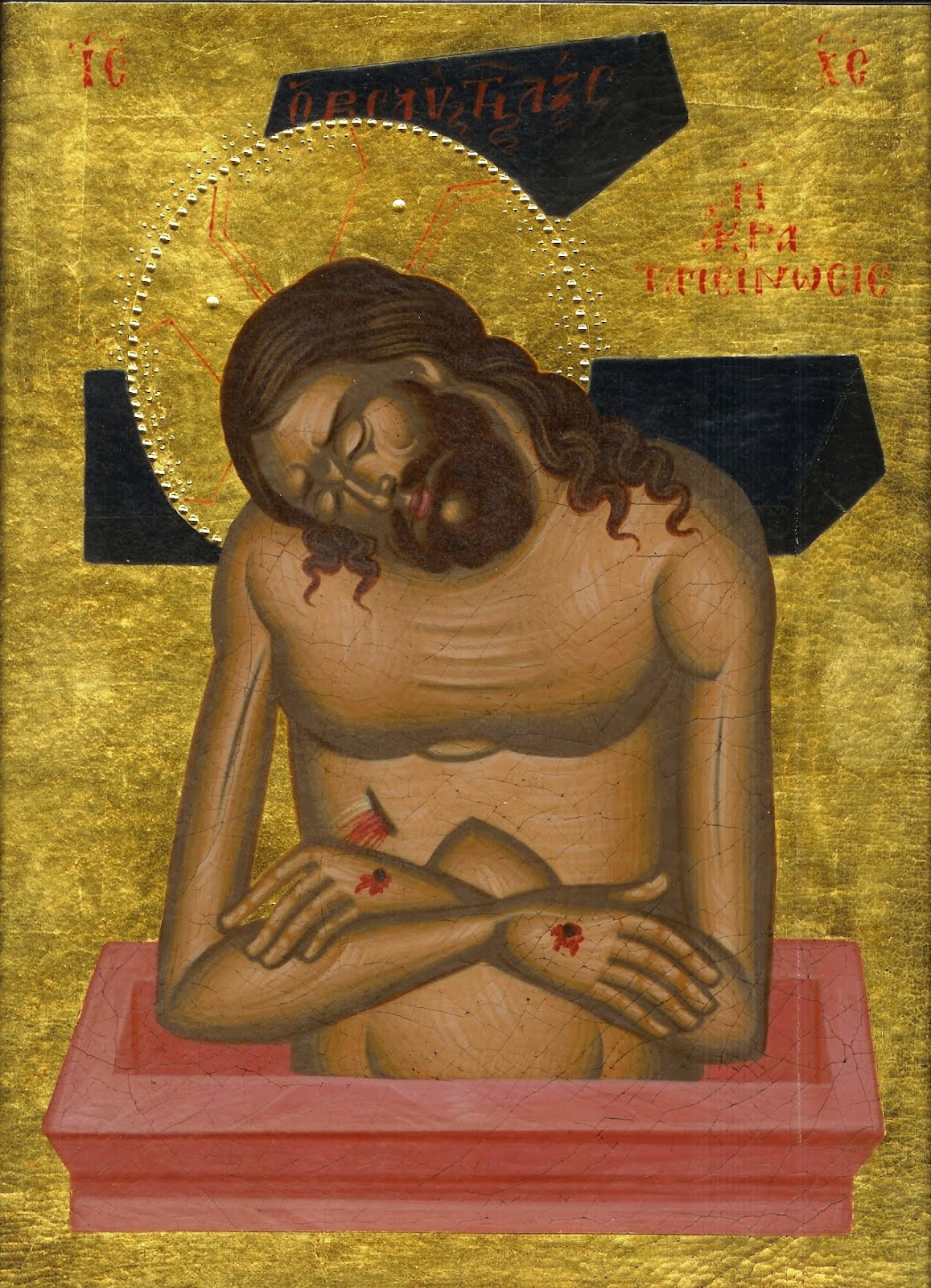

Fasting in the Eastern Churches is a tool for retraining the ego. It is a way of curbing the “I crave” in each of us and doing it together as a community. Fasting is a type of self-denial, an imitation of Christ’s own emptying Himself in order to share our human condition. The liturgy expresses this poetically: “The flower of abstinence grows for the entire world from the tree of the Cross. Let us then accept the Fast with love and take pleasure in the fruit of Christ’s divine commandments” (Orthros, First Wednesday of the Fast). The self-emptying of the cross bears fruit in us when we strive to empty ourselves through fasting.

People with real health issues will always receive a blessing to eat meat or dairy during the Fast but for most people, their reluctance to avoid these foods – and for forty days, at that – is because they don’t want to give up the taste. If we look to the Fast in the way that the Church does, as an exercise in curbing our ego, we may well decide to avoid meat and dairy “look-alikes” as well.

The teaching on fasting in the Sermon on the Mount, read at today’s Liturgy, concludes with the admonition, “Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal” (Matthew 6:19). Fasting is a school in which we try to live by this precept. In our affluent society most of us have some “treasures on earth” which we are reluctant to give up. Fasting helps us learn that we can in fact live without some of the things on which we base our way of life.

Fasting and Compassion

In the Gospel Christ admonishes us to avoid making a show of our fasting. In ancient Israel people often manifested their sorrow or repentance by tearing their garments or wearing sackcloth and smearing their faces with ashes. Christ taught the opposite: “But you, when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face, so that you do not appear to men to be fasting” (Matthew 6:17-18).

The Church encourages us to do the same, and specifies the ointment we should use: “Let us anoint the head of our soul with the oil of loving compassion” (Canon, First Monday of the Fast). In Greek the words for oil and mercy are virtually identical, giving rise to the idea that the joy of the season is to be found in extending compassion to the needy. “When you give, give generously, your face lit up with joy. And give more than you were asked for…” (Isaac the Syrian, Ascetic Treatises, 23).

The frequency of Lenten charity suppers or alms boxes in our churches are expressions of this sentiment.

Compassion has been defined as “the deep awareness of the suffering of others coupled with the desire to relieve it.” It is much more personal than writing a check or dropping off a donation to the local thrift store. Compassion is what motivates the coming of Christ in the flesh. “If He came down to earth, it was out of compassion for the human race. He suffered our sufferings before suffering the cross, even before taking our flesh. If He had not suffered, He would not have come down to share our life with us” (Origen, Sixth Homily on Ezekiel 6,6). Imitating the compassion of Christ, then, means becoming personally involved with those you seek to help, even to the extent of sharing their condition. For most of us, learning to do so might take a lifetime of Lents.

It has long been the custom to speak of the Corporal and Spiritual Works of Mercy, ways of showing compassion that are within the reach of every believer. They are:

Corporal (physical) Works of Mercy:

- Feeding the hungry

- Giving drink to the thirsty

- Sheltering the homeless

- Clothing the naked

- Visiting the sick

- Visiting the imprisoned, and

- Burying the dead

Spiritual Works of Mercy:

- Admonishing the sinner

- Instructing the ignorant

- Counseling the unsettled

- Comforting the sorrowful

- Bearing wrongs patiently

- Forgiving all injuries, and

- Praying for the living and the dead.

Can at least one of these form part of your exercise of the Great Fast?

Recent Comments