Source: annalesecclesiaeucrainae.blogspot.com

At the beginning of the current year, Nykyta Budka’s diary from his seminary-university years (1902–1905) was discovered by the archivist of the Archeparchy of Winnipeg, Gloria Romaniuk. The 20 by 17cm notebook had been left by Bishop Budka at his chancery residence at 511 Dominion Street in Winnipeg, when he departed for Europe in December 1927. Having been ordered to resign as bishop for Canada in November 1928, Budka was never permitted to return nor retrieve any of his belongings. His personal property was entrusted to the care of his brother Danylo, who had emigrated from western Ukraine (part of Poland, at the time) to Canada, earlier that year. Although some of the bishop’s records passed to his successor, many of Budka’s effects were sold off and a quantity ended up in the possession of Ukrainian poet and church goodsman, Yakiv Maydanyk. In the late 1950s Budka’s second successor, Metropolitan Maxim Hermaniuk, repatriated many of these items to the ownership of the Ukrainian Catholic Church.

During the 1980s, the first archivist of the Archeparchy, Sister Cornelia Mantyka, oversaw a complete reorganization of Bishop Budka’s correspondence, but the university diary was not inserted in this archival collection. Metropolitan Maxim had kept them in his possession and, following his death in 1996, the diary was placed in one of several boxes containing his books and papers. After Hermaniuk’s successor, Metropolitan Michael Bzdel, retired in 2006, the boxes were consigned to the care of archeparchial archives. At first, they were stored in a room on the second floor in the old bishop’s palace, near the chapel. In the spring of 2015, the archivist began examining the contents of the boxes and discovered the diary. Romaniuk was able to identify the contents by Budka’s name, clearly written on a number of theology textbook receipts and on other loose papers inside the notebook. She was then able to identify the handwriting in the journal and, from a cursory examination of the contents and the title “Моя теольоґія в Інсбруку” (my theology [studies] in Innsbruck), realized that she had discovered a memoir from Budka’s student days.

Given this source’s historical importance, Romaniuk immediately brought it to Metropolitan Lawrence Huculak and noted the journal’s discovery in her March 2015 report from the Archives, indicating that it would be added to the Nykyta Budka fonds (NB) within the Archives of the Archeparchy. Metropolitan Lawrence gave his blessing to me to consult the work. Upon my arrival in Winnipeg at the beginning of July, I digitally photographed each page and loose insert, which included textbook receipts, some history and theology class notes, and a photograph taken with two other men in the mountains (perhaps the Alps) during a vacation or outing.

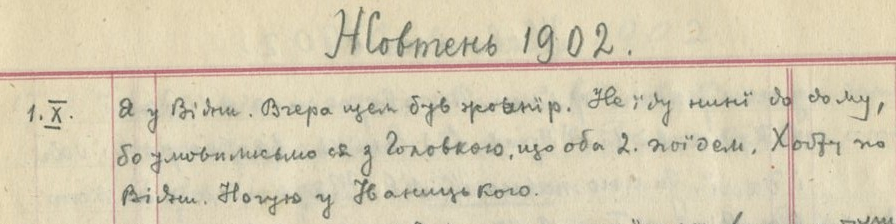

The diary begins in Vienna, the day after Budka completed his year of military service, on 1 October 1902, and ends on 23 July 1905, the day he passed his last theology exam and was packing his books and personal effects, in preparing to leave Innsbruck. At the time, Budka’s written language was an archaic, western Ukrainian dialect.

Most of Nykyta Budka’s extant writings are in the form of official correspondence with hierarchs, clergy, church congregations, and individual faithful. This diary represents a rare example of his personal reflections, which he committed to writing primarily for private reference. It is possible that Budka, whose correspondence contains several references to his awareness of the importance of historical witness, also intended these reflections for posterity.

Alpine outing circa 1903

Having only been discovered this year, this important source was not available to me when I was composing God’s Martyr, History’s Witness. Still, the information contained in the diary does not change the overall narrative of this biography for the years 1902–1905, which Prof. Oleh Turiy and I had based mainly on letters from Budka to Sheptytsky from the Central State Archives of Ukraine in Lviv (ЦДАУЛ).

Nevertheless, the diaries contain more frequent personal information absent from Budka’s formal correspondence. The diary clarifies certain facts which were missing from my research. Among these details are the following: detailed chronology of his life as a seminarian and university student; the identities of his closest friends and associates during these years, in particular future-bishop Yosyf Botsian; additional information pertaining to his decision to pursue doctoral studies in Vienna, following the completion of his initial theological curriculum in Innsbruck; that his 18-year-old sister was named Hanya (Anna), and that the cause of her untimely death in the Spring of 1904, was an aneurism. Budka was not able to attend the funeral but had the opportunity to visit his grieving parents shortly thereafter, during the university Easter break.

The fact that Blessed Nykyta kept a diary in his youthful years raises the possibility that he might have committed other personal reflections to writing in later years, which have not yet come to light. If such documents exist, did they survive and where are they now? A closer examination of the Budka papers in the Lviv State Archives as well as unexamined materials in Ukrainian Catholic archives in Canada might, perhaps, result in the unearthing of as-yet-undiscovered writings of this important historical and religious figure.

Recent Comments