Article by: Fr. Stephen Freeman

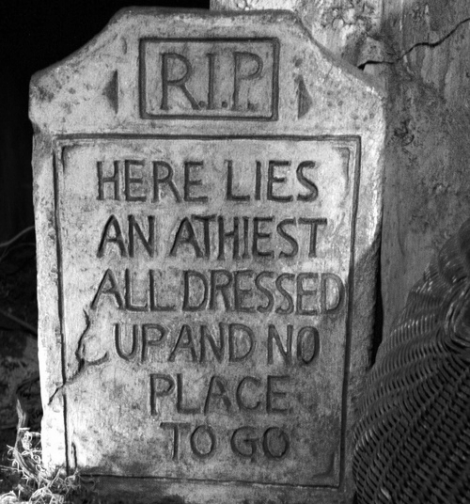

Almost no event shatters the confidence of the secular world like death.

Regardless of a person’s achievements, fame or wealth, death not only destroys but threatens to mock. Many older funeral customs evolved in a relatively non-secular context. It is not surprising that funerals in the secular world are changing quickly: their content speaks volumes about the nature of secularized religion.

A 2009 article states:

Nearly 50 years ago, only 5 percent of the funerals in North America involved cremation. That percentage increased to 20 percent 30 years later, and in the past 15 years that percentage is pushing past 40 percent, which amounts to about 1.5 million cremations by next year.

I have served as a pastor in the American Southeast since 1980. Over the past 32 years I have seen a vast change in popular thought about funerals. Orthodox tradition and practice is quickly being viewed as too expensive, too focused on religion, and too concerned with the body.

Contemporary funerals (frequently termed a “celebration of life”) often have no “body” present. As memorials, the emphasis is on remembering the past – and in the most positive manner. Some celebrations have the feel of a “production,” complete with large projection screen and digitally produced music. Most funeral homes are glad to provide the production work.

In contrast, an Orthodox funeral concentrates on a different memorial. It is God’s eternal memory of those who have fallen asleep that is asked. Our own memory is weak, and biased, itself destined to fade within less than a life-time.

I have often been told that a funeral is “for those who grieve.” This is a deeply secular understanding of death. Secularism thinks that those who have died have need of nothing – they are gone as if they never were. Those who remain have the burden of guilt and grief – it is their needs that should be our present concern.

Death challenges the secular world at its weakest point. Secular life is essentially meaningless. There is an old phrase which describes those who fear something so much that they seek to ignore its presence as “whistling past the graveyard.” It is even easier to whistle past the graveyard if you never go near one.

Iron and Wine (2004) offered the world perhaps the first love song about cremation:

She says “If I leave before you, darling

Don’t you waste me in the ground”

I lay smiling like our sleeping children

One of us will die inside these arms

Eyes wide open, naked as we came

One will spread our ashes round the yard

The song has the honesty of recognizing that death at least yields something tangible.

The inherent meaninglessness of an existence that has no transcendence – nothing beyond itself – offers the modern world great temptation. If we will have no God, then we will invent lesser gods and serve them instead. Radical environmentalism has become a growing substitute for God. Some lessen their “carbon footprint” by extreme measures – limiting family size by any means possible. Of course, the ultimate lessening of our footprint is to remove ourselves from the planet – to what purpose? Indeed, what purpose the planet itself? Who would laud such noble sacrifice?

The transcendence of a two-storey world – one in which this world only has meaning because of the “next” world – is equally flawed. The world in which we live is not only transcended – it is positively devalued (except in those accounts in which eternity itself is determined within the short span of life on earth). In traditional Western Christianity, this two-storey account of life and death predominates. The world in which we live has no connection to the world in which God dwells, apart from moral concerns. There is no sacramental union, only the token appearances that appear magically in churches from time to time.

In the traditional theology of the Eastern Church, this world and the “next,” are not two worlds. We use the language of place (heaven and earth) for lack of language not for accuracy. There is more to the created order than we see (“all things visible and invisible”). But that which is not seen is not inherently separate from that which is. Sacrament (mystery in the East) is a way of describing the relationship between what is seen and what is unseen. Everything is sacrament, icon and symbol.

In such a setting, death is a change, but not an end. That which we see, the body, remains important and worthy of honor. A funeral, the service of remembrance, is a sacramental gathering in the presence of God. The body is honored, even venerated. The life of remembrance, eternal remembrance, begins.

My wife and I have a fifth child, one who died in the 5th month of his gestation. I held him at the time of his still birth. We mourned his loss, and gave him a name. We entrusted his life to the good God who gave him to us. The only relationship I have had with him has been one of remembrance. Each day in my prayers he is remembered along with my grandparents, my parents and in-laws who have gone before. They are not a part of my past, but a part of my present, particularly when I am awake and stand before God, seeing the world as it truly is.

The fiction of sentimentality and the emptiness of secular mourning quickly fade before the great presence of God. The proclamation of Christ’s resurrection is no pious notion about the world to come. It is the triumph here and now over death – the presence of Life pressing in on us – lifting up the world into the fullness of its meaning – gathering together all things in one.

Memory eternal!

Recent Comments